“Who are the peacemakers in times of haunting wars?” Olena Tovianska asks from Irpin, Ukraine. She does not ask as a distant observer or a detached theologian, but as someone living inside the question. War is not an abstract concept where she lives; it constructs daily reality. Olena is a translator by profession, but her ministry reaches deeper—she explores how the performing arts can help traumatized communities begin to heal.

Her words do not deny the ugliness of war. They refuse to look away from wounds and tragedies. Instead, she asks whether there are people courageous enough to stand with victims and confront aggressors. Implicit in her question is a harder one: what happens to human beings when power is exercised without accountability, restraint, or compassion?

The suffering Olena describes is not unique to Ukraine, even if the bombs and ruins are more visible there. Around the world—and closer to home—suffering often begins with a failure of leadership to live as God intends we live together and to protect rather than exploit the vulnerable. It’s happening to immigrants living in Minneapolis who came to this country with great anticipation

Research consistently shows that people do not leave their homelands casually. Studies of immigration to the United States reveal that while economic opportunity matters, a significant number of immigrants cite violence, insecurity, and the collapse of basic freedoms as central reasons for leaving. Immigration, for many, is not ambition—it is escape. It is an act of survival in response to cruelty, corruption, or fear that has become unbearable.

That story continues once people arrive here. Journalists have documented families who fled violence, followed every instruction given by the U.S. government, attended hearings, checked in regularly, and tried to build quiet, faithful lives—only to find themselves suddenly detained, separated, or living under constant threat.

Moreover, the suffering caused by aggressive immigration enforcement is not limited to those who lack authorization. In practice, it falls most heavily on people of color from countries viewed as disposable or suspect by those in power. The result is a form of suffering that experts describe as chronic and corrosive: parents afraid to drive, children anxious about school, entire communities learning to remain invisible. Like war, it is suffering shaped by decisions made far away, by leaders who will never meet the people who bear the cost.

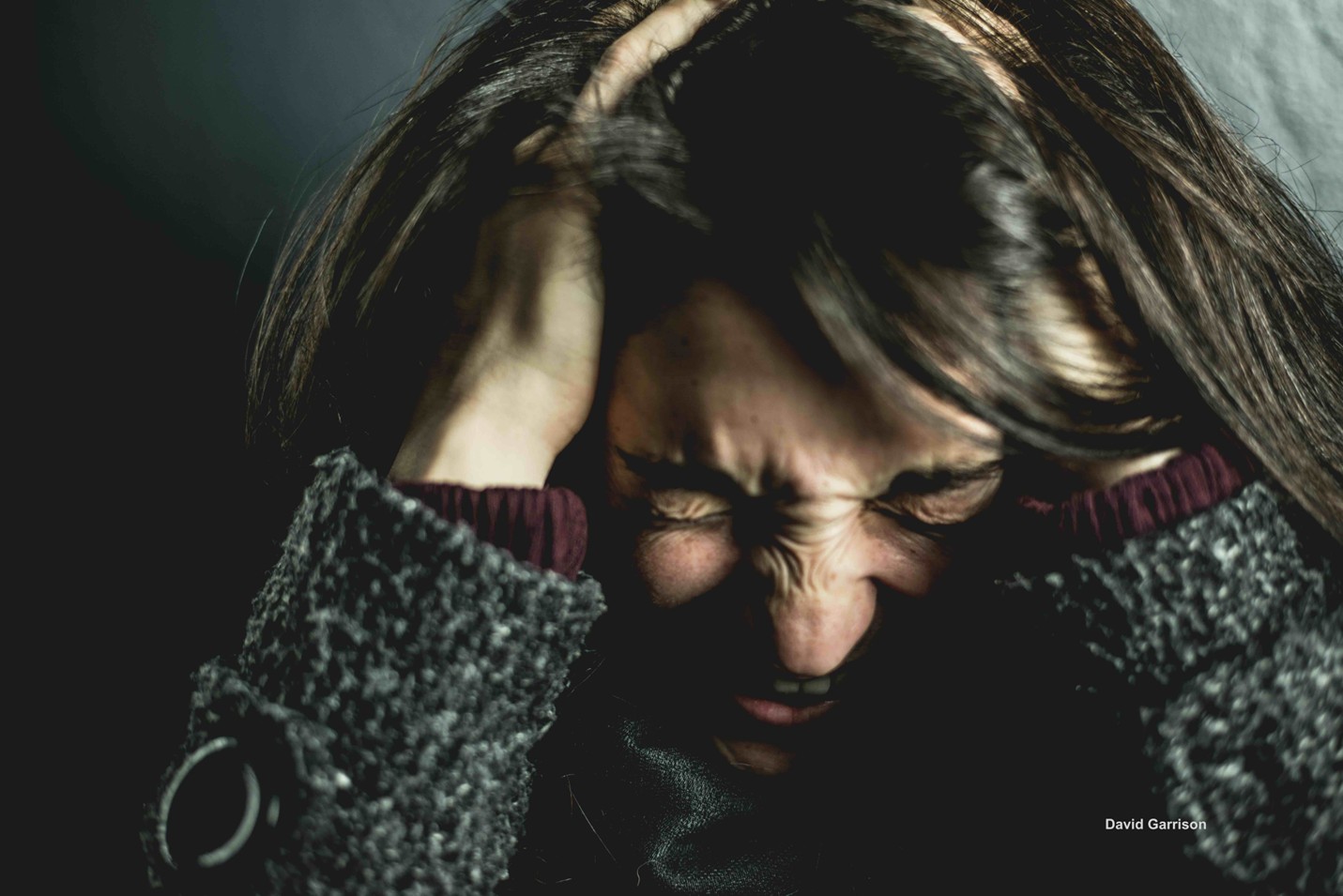

Human beings respond to this kind of suffering in predictable ways. Trauma specialists tell us that prolonged fear and uncertainty rewire the nervous system; people live in a constant state of alert, unable to rest. Sociologists note that when suffering is paired with powerlessness, it erodes dignity and hope.

Those watching from the outside often respond differently. Some turn away, overwhelmed by the scale of pain. Others explain it away, insisting it is necessary, deserved, or inevitable. Still others grow numb, scrolling past one more story of loss because paying attention feels too heavy. Yet voices like Olena’s refuse that numbing. They insist that suffering is not a statistic or a political inconvenience—it is a moral summons.

Across war zones and immigration courts alike, the pattern is clear. When leaders cling to power through fear, ordinary people suffer. And when suffering is ignored, justified, or hidden, it multiplies. The question Olena asks from Ukraine echoes here as well: Where are the peacemakers? Who is willing to face the ugliness without looking away, to plant seeds of courage, to stand with the wounded and name the truth about what is being done to them?

At the same time, we need to be honest about something else. For many of our neighbors here in Flint, especially those who rely on shelters and warming centers, like the one run by Catholic Charities, suffering is not something they read about in the news. It is something they wake up with in their bodies. Chronic illness, untreated pain, exhaustion, anxiety, and the daily stress of not knowing where they will sleep or how they will be cared for weigh heavily on them.

For someone already overwhelmed by their own survival, stories of war in Ukraine or immigrant families facing deportation can feel distant, even unbearable. It is not indifference; it is depletion. Compassion is hard to extend when every ounce of energy is already spent just getting through the day.

The same is true for many who will hear or read these words. Much suffering is hidden. Some are grieving losses no one else sees. Others are carrying medical diagnoses, financial strain, fractured relationships, or deep loneliness in silence. For them, global suffering does not always put their pain “in perspective.” More often, it adds to the weight.

Scripture never asks suffering people to minimize their own pain in order to care about others. Instead, it recognizes that suffering has many faces—and that God’s concern is wide enough to hold them all at once.

Matthew begins his gospel with a story that feels just close enough to the cruelty we’re witnessing today to feel like a foreshadowing of things to come. Matthew tells us that when visitors from the East arrive in Jerusalem, asking about a newborn king, King Herod is not curious, but terrified. After Jesus was born, the king feared his power might be challenged, so he ordered the slaughter of the children of Bethlehem. Jesus taught, healed, and called disciples in a world aching with grief.

Matthew includes a haunting reference to an older Scripture—words about Rachel weeping for her children and refusing to be comforted. Matthew is not quoting poetry at random. He is reaching back into Israel’s memory of trauma, exile, and loss, reminding his readers that the suffering surrounding Jesus is not new, and it is not ignored by God. To understand what Matthew is doing, we need to listen carefully to that earlier story—and to why tears, not triumph, are the first sounds that surround the birth of the Savior.

When Matthew quotes, “A voice was heard in Ramah, wailing and loud lamentation, Rachel weeping for her children,” he is reaching back to the prophet Jeremiah. Rachel, one of Israel’s matriarchs, had long been remembered as the sym bolic mother of the nation. In Jeremiah’s time, her “weeping” names one of Israel’s deepest collective traumas: the Babylonian exile.

Ramah was a place where captives were gathered before being marched away from their homes, their land, and their future. Parents watched children disappear. Families were torn apart. The loss was so profound that Jeremiah describes Rachel refusing comfort—not because comfort is cruel, but because grief that deep cannot be rushed.

Scripture does not ask us to pretend this grief isn’t real. In fact, it gives us language when our own words fail. Psalm 13 cries out, “How long, O Lord? Will you forget me forever?” This is not a loss of faith, but it is faith refusing to lie. Like Rachel’s tears, this lament is allowed to stand. God does not interrupt it with explanations. God receives it.

In Jeremiah, Rachel’s tears are not the end of the story. God speaks words of promise: “Keep your voice from weeping… There is hope for your future.” Importantly, the hope does not erase the grief. God does not scold Rachel for her tears or tell her to move on. The promise comes after the lament, not instead of it. In Israel’s faith, grief is not a failure of belief—it is part of faithful remembering. God allows the tears to stand.

A sound is heard in Ramah, the sound of bitter weeping. Rachel is crying for her children; she refuses to be comforted, for they are dead.

Matthew 2:16-18

This matters for anyone who is suffering now. Jeremiah does not ask wounded people to pretend the exile wasn’t devastating. He gives them language for their pain and assures them that God hears it.

When Matthew brings Rachel’s weeping into his Gospel, he does something striking. He places Jesus’ story squarely inside a history of unresolved grief. Herod orders the killing of children not because they are dangerous, but because he is afraid. Like tyrants before him, he confuses vulnerability with threat and responds with violence. Mothers weep. Families mourn. Innocent lives are lost. And Matthew does not soften the horror.

Just as important is what Matthew does not say. He does not explain why God “allowed” this to happen. He does not suggest the suffering was necessary or redemptive in the moment. He does not rush us toward resurrection language or silver linings. Instead, he insists that the birth of Jesus occurs in a world where abusive power causes suffering, and leaders still sacrifice the vulnerable to preserve themselves, and where grief is real and justified.

For people suffering today—whether from war, displacement, poverty, illness, or quiet despair—this honesty matters. Matthew refuses to turn suffering into a theological puzzle to be solved. He tells the truth: the coming of Christ does not immediately end tyranny or prevent tragedy. What it does is place God inside the story of suffering, not above it or outside it.

It can be tempting, in the face of suffering that seems overwhelming, to reach for familiar spiritual phrases — “God has a plan,” or “It will all work out for good.” But too often these words end up minimizing pain, as if suffering must be explained rather than felt.

I would be remiss if I didn’t lift up the story of five-year-old Liam Conejo Ramos and his father, Adrian Conejo Arias. The two were taken into custody recently in Minnesota by federal immigration agents. They were not arrested for violence or for wrongdoing of any kind. In fact, they were in the midst of an active asylum case that they had pursued legally and patiently.

Images of Liam, wearing a blue bunny hat and a Spider-Man backpack as he was led away by agents, quickly became a symbol of how vulnerable lives are affected by enforcement practices enacted by the current administration. Community members and school officials reported that the boy had just come home from preschool when the agents approached, and observers raised serious questions about the way the operation was conducted.

The outcry that followed was neither quiet nor abstract. People — from teachers to lawmakers to advocates — spoke up. Protests formed outside the detention facility in Texas where they were held, with demonstrators insisting that children are not criminals and calling for humane treatment. State and national leaders pressed for accountability and urged respect for the family’s right to due process. A federal judge ruled that neither Liam nor his father could be deported or transferred while their case proceeds in court, affirming the basic legal principle that no one can be removed from the country without due process of law.

These responses matter for our vision of what faithful presence looks like. Courageous witness is not found in denial of suffering, nor in shrugging helplessly at cruelty, but in speaking truth — even when it is uncomfortable or costly. People came forward despite their fear, despite knowing that raising their voices might invite backlash. Their actions reflect what our companion book describes as hope that engages reality rather than escaping it — the kind of hope that stands with suffering people instead of patting them from afar with clichés.

And this is precisely the kind of vision God casts for us: a vision in which suffering is acknowledged fully, where power is held accountable, and where the community of faith refuses to let injustice go unnoticed. To stand against suffering is not the same as believing suffering is absent. It is saying — with our actions, our voices, and our compassion — that cruelty does not have the last word and that God’s presence is with the wounded.

Nadia Bolz-Weber, in this week’s chapters from our companion book, reminds us that God does not hide uncomfortable truths behind platitudes. God stands in the midst of suffering, with those who mourn and with those whose lives have been caught up in cruelty and fear, and calls us to stand with them, too.

God is with those who suffer in Ukraine, with families seeking refuge, and with every neighbor whose pain is unseen or unheard. God calls us not to minimize their experiences but to walk alongside them — advocating, witnessing, and giving voice to their dignity. This is what it means to see suffering the way God sees it: not as a test to be explained, but as a reality to be met with courage, compassion, and justice.

For those at the warming center in Flint, for those navigating chronic illness, for those carrying grief or fear they rarely name out loud, this story does not demand more than they can give. It does not ask them to fix the world or feel compassion they do not have the energy to feel. It simply says this: God sees suffering clearly, names it honestly, and refuses to look away. Rachel’s tears matter. Ukrainian tears matter. Immigrant tears matter. Your tears matter.

Matthew’s Gospel begins not with triumph, but with mourning—because God is not afraid of grief. And because salvation does not begin by denying how broken the world is, but by entering it fully.

From the beginning of Jesus’ story, Matthew tells us that God chooses to enter a world shaped by tyrants rather than wait for a safer one. Rachel’s tears are not dismissed. Families fleeing violence are not invisible. Those who suffer in body, spirit, or circumstance are not asked to justify their pain or find meaning in it too quickly. God stands with those who suffer—and stands against the forces that cause suffering. That is not sentiment. That is the moral arc of the gospel.

So what does faith look like in a world like this? It does not require us to carry suffering we do not have the capacity to carry. It does not demand perfect words or heroic action from everyone. What it does call for is honesty, presence, and courage—expressed differently depending on who we are and where we stand.

You can join us each Sunday in person or online by clicking the button on our website’s homepage. Click here to watch. This button takes you to our YouTube channel. You can find more information about us on our website at FlintAsburyChurch.org.

This is a reminder that we publish a weekly newsletter called the Circuit Rider. You can request this publication by email by sending a request to FlintAsburyUMC@gmail.com, or let us know when you send a message through our website. We post an archive of past editions on our website under Connect – choose Newsletters.

Pastor Tommy

Nadia Bolz-Weber. Accidental Saints: Finding God in All the Wrong People. NY: Convergent Books, 2015. (ISBN 978-1-60142-755-7 ).

Olena Tovianska. “Unshaken.” The Upper Room Disciplines 2026. Nashville: The Upper Room, 2025.

Jesus Jank Curbelo and Nicholas Dale Leal. “Liam Conejo Ramos: The face of the hundreds of minors in immigration custody under the Trump administration.” © EL PAÍS USA Edition, Jan 27, 2026. Retrieved from: link